At the end of March, 2021, COVID-19 has killed more than 9,000 people in South Carolina, and almost 8,000 of them are people above the age of 60.

Reconcile that with the Pew Research Center’s findings that once above the age of 60, access to and ownership of smartphones or any device connected to the internet drops sharply as age increases.

Where this overlaps dangerously is in the middle of the COVID vaccine rollout, which requires residents to register through their phones, tablets, or computers. In a state where broadband access is being addressed more urgently by federal and state officials, huge parcels of South Carolina between Newberry and Jasper counties still have zero access to the internet, according to coverage maps by Palmetto Care Connections (PCC), a nonprofit advocate for equitable and wide-reaching broadband access in the state.

Kathy Schwarting, CEO of PCC, says that this puts residents – particularly rural seniors – in a bad spot.

“There’s the access issue,” Schwarting says. “Whether or not your area even has the ability to have internet. If you live out in the country, outside of the city limits, you may not even have fiber; and it’s very expensive to run it.”

But there’s also an age issue, remember. The Pew study shows that in 2017, the last year data is available, 67 percent of seniors were on the internet but 51 percent had access to broadband. Those numbers are likely a combination of choice and circumstance and may have changed in the intervening years, but there are, nevertheless, seniors who are simply not connected, at a time when the way to get registered for a COVID vaccination is online.

Schwarting has an aunt in her 70s who wanted to get vaccinated and had to call the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) on the phone. The department initially told her she needed to sign up online, but Schwarting’s aunt has no computer and no internet-capable phone.

Schwarting says DHEC brought her aunt into an office and registered her in person. And while she’s happy it worked out for her aunt, Schwarting knows not everyone who’s offline will be able to do that. For rural seniors in particular, physically getting to a DHEC office could be a near impossibility.

Schwarting says several seniors without email addresses or even a connection have enlisted help from their children and grandchildren to register. For those who can get that kind of help, great, but again, she says, not everyone has someone connected whom they can call upon for help.

Cost, of course, is another issue. Even with access to some kind of reliable internet, it can be expensive. High-speed internet, which is often needed to navigate websites these days, is considered anything above 25 megabytes per second. Some plans in South Carolina run at 300mbs. The more mbs, the more money.

Monthly plans for low-income residents can start at $10 (or in some cases be essentially free). Some providers temporarily expanded eligibility to broadband because of the pandemic.

AT&T, one of the major providers in the state, did this. Lead Public Relations Manager Megan Daly said in a statement to South Carolina Public Radio that the company’s Access from AT&T program was offered to households participating in the National School Lunch Program and Head Start, “for $10 a month or less. Also, for a limited time, customers at locations with available AT&T Internet speeds above 10 Mbps may be eligible for a speed upgrade up to 25 Mbps.”

But if you don’t qualify for a low-income plan, broadband service can be pricy. It’s not unusual for South Carolinians to have plans costing around $75 a month in some well-connected areas. And, of course, plans expanded because of the pandemic will not be permanent, which, Schwarting says, could become problematic for unconnected lower-income residents looking to access medical records or find work after life moves past COVID’s disruption.

“If you are living paycheck-to-paycheck,” she says, "and you are trying to balance getting your medications, paying your light bill, paying your mortgage, making sure you have groceries, $75 is an awful lot of money. And [a $15] increase is a lot of money in a house where they don’t have extra money.”

According to BroadbandNow, South Carolina ranks 31st among U.S. states in high-speed connectivity, and about 53 percent of residents have access to a wired, low-price plan.

Connecting with the Unconnected: ‘Word of Mouth is Powerful’

An unexpected side-effect of the pandemic is that for as much as it put a spotlight on the need for technology access, it also reminded us that we still need analog options for getting in touch with people in a crisis.

Social media is the favored distribution method of health agencies, social services workers, news companies, and whoever else wants to get the word out about something. The reach is immense and immediate, but it does zero good for anyone who isn’t connected.

“Boots on the ground,” says Davia Smith, PCC’s director of education. “Social media works for some but it doesn’t work for all.”

Smith says that meeting people where they live – the grocery stores, churches, pharmacies – is the key to getting through to communities that might be cut off. That includes poor communities, communities of color, and rural neighborhoods, which all share something important to remember – a tendency to trust most in people they already know personally.

Getting to people in these communities is a clearly hefty task. But Smith says it’s necessary, especially in light of the continuing disappearance of one particular source of information.

“You have some communities that no longer have a local newspaper,” she says.

And even in places where local papers still exist, they are usually weeklies, which Smith says can create troublesome lags when people need to receive urgent information. So social and health workers, she says, need to ramp up their alternatives for how to get information to residents, and need to stop thinking that a website or an app solves every problem.

“We can’t stay behind the computer screen and expect everything to get done,” she says. “Word of mouth is powerful.”

DHEC, for its part, appears to have learned this lesson some.

In a statement, DHEC said:

We work to get current messaging to people who don't rely on the internet for their news and information by way of:

- signage at gas stations (targeted rural areas)

- billboards (target rural areas)

- advertisements in every weekly newspaper in the state

- radio PSAs

- TV PSAs

- direct mailers

- ongoing partnerships with local organizations that promote our messaging within their communities

- continued partnerships with our state's faith-based organizations to help share important information and resources

- We partner with the nonprofit Hold Out The Lifeline (HOTL) to support grassroots statewide efforts directed toward African American churches and community groups. Among the many services offered, HOTL is conducting virtual briefings, distributing some of DHEC's hardcopy resources and materials, and distributing PPE (face masks, hand sanitizer, gloves etc.) HOTL also provides church leaders with a toolkit to help them plan educational sessions that help inform their members about COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccine. In January alone, it's estimated that HOTL reached nearly 30,000 congregants with current DHEC messaging.

- information at public transit hubs

- shared information with the S.C. Department of Commerce and DHEC's regulated business community to share with employees (breakroom signage and take-home literature)

- sharing information and resources with the S.C. Commission for Minority Affairs, S.C. Department of Aging, Office of Rural Health, S.C. Department of Employment and Workforce, AARP, PASOS, housing authorities, public transportation systems, etc., to share current key messaging and phone numbers for accessing additional information.

Smith sympathizes with anyone trying to get real information out to communities that aren’t as well-connected. She says that between misinformation, constant updates of real information about what’s safe or where and when a vaccination event will happen, and the sheer volume of information hitting people (especially, ironically, the connected), getting good information through to residents is a tall task, but one that demands getting done right.

She says that as tech access becomes more ubiquitous, it will be important to remember that tech is not a Messiah, but a tool.

“I remember when stores … put in the U-Scan™ registers, and it was like, ‘Technology is going to take everyone’s job,” she says.

That didn’t happen, of course, and that’s her point.

“COVID has shown us that technology is a useful tool, but it’s not going to replace everything,” she says.

Efforts to Expand Access

One positive thing about the pandemic is that its main lesson about internet access – that it’s not a luxury anymore, but a necessity – appears to have gotten through to lawmakers who could do something about it.

Both of South Carolina’s U.S. Senators, Lindsey Graham and Tim Scott, Republicans, co-sponsored the Governors’ Broadband Development Fund, along with Sen. Mark Warner, Democrat, of Virginia. In December, the Federal Communications Commission granted the measure $121 million to expand rural broadband in South Carolina. The bill aims to get access to almost 109,000 homes that otherwise, according a statement Graham made, “might as well be on the moon when it comes to getting high-speed internet service.”

In mid-January, the outgoing Trump administration announced a $1.6 million grant to the Lancaster Telephone Company to deploy a fiber-to-the-premises network to connect 5,574 people, 20 businesses, 17 farms, and three educational facilities to broadband in Lancaster and Chester counties.

While measures like these certainly can help, South Carolina still has quite a way to go. The State newspaper reported last June that connecting all of South Carolina could be an $800 million endeavor. An ambitious plan introduced by U.S. Rep. and House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn (D, SC-6th), the Accessible, Affordable Internet for All Act, looks to invest $100 billion to build high-speed broadband infrastructure in unserved and underserved communities all over the country.

That bill was introduced last June and is making the rounds among the Biden administration's American Rescue Plan.

And South Carolina’s state leaders have looked to tackle the issue of broadband access as well. In September, Gov. Henry McMaster signed the GREAT (Growing Rural Economies with Access to Technology) program into law. It looks to set the stage for a codified broadband access law in the state.

And the state’s 2021 budget features a $30 million safeguard to expand rural broadband to schools and businesses.

All of this is good news to guys like Graham Adams, CEO of the South Carolina Office of Rural Health (SCORH), who says that one of the pandemic’s few positives is the attention broadband access to rural America has gotten.

“[It’s] a much more recognized problem,” Adams says. “There’s a lot more attention on the lack of broadband in rural communities. The whole world was thrown into telecommuting and tele-learning; we all gained a greater appreciation for the importance of connectivity in the home.”

Something Adams hopes people in general come to understand better as access accelerates is that rural communities do want broadband. He says it’s not a matter of not wanting so much as a matter of simply not having access nor the ability to pay for it.

For now, he is glad to see progress being made, including in efforts like the joint SCORH, PCC, South Carolina Rural Innovation Network effort to map access points in Barnwell and Williamsburg counties. Those are two areas plagued by lesser tech access and lesser tech literacy, which Adams also says needs to be a major component of broadband expansion – because tech access won’t do anyone any good if no one can afford it and if no one knows how to use it.

A Small Data Snapshot

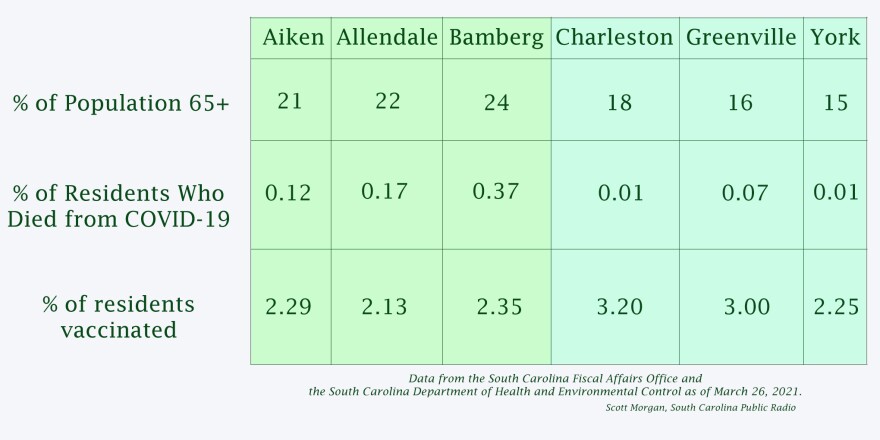

The caveat with this section and its accompanying graph is, don’t try to apply it too broadly. But as a way of illustrating a piece of the intersection of age, access, and vaccination, the data points do show a couple interesting things, as of March 26, 2021.

Allendale, Aiken, and Bamberg counties, all mostly rural, have some of South Carolina’s largest areas without internet coverage; they each also have, according to data from the South Carolina Fiscal Affairs Office, senior populations above 20 percent – and, according to data from DHEC, have higher rates of death from COVID compared to three of the most connected counties in the state, Charleston, Greenville, and York. All three of these counties have senior populations below 20 percent.

While the dataset is too small to extrapolate any sweeping trends, there are also some correlations between how wired a county is and the percentage of that county’s residents who have been vaccinated at least once. Only York County, which is highly connected but has a relatively low vaccination rate, stands apart.

Addendum, March 26, 2021: On the day this story published, U.S. Senators Lindsey Graham and Tim Scott of South Carolina announced the $20 billion State Fix Act to build 5G fiber infrastructure in underserved rural communities.