For almost a month, students in South Carolina have received classroom instruction and completed assignments from the safety of their homes. In March, states across the country started closing schools to slow the spread of the Coronavirus. Since March 16, students in South Carolina have engaged in some form of e-learning, but experts say the lack of access to broadband in rural areas creates barriers for many.

One of the first online events for kids was a lunch-time drawing session with celebrated children’s book author and illustrator Mo Willems. “Lunch Doodle with Mo,” offered free, virtual sessions published to the Kennedy Center’s YouTube channel every day at 1p.m. ET. In the first episode, Willems (the education artist-in-residence at the Kennedy Center) showed kids how to draw one of his most famous characters—the pigeon.

Other virtual events allowed quarantined kids and parents to interact with artists and musicians during live mini concerts; see local meteorologists give presentations about weather; and take dance instructions from Emmy-award winning actress and choreographer Debbie Allen.

“My oldest missed her dance class, and is probably going to miss several other dances classes.”

Columbia resident, Roshanda Pratt, said her daughter dances with a praise ministry team and also does ballet. She’s using the internet to help keep her connected to her regular activities.

“I found a teacher out of Tennessee who offers P.E. courses; so he’s doing YouTube videos for P.E. classes,” Pratt said.

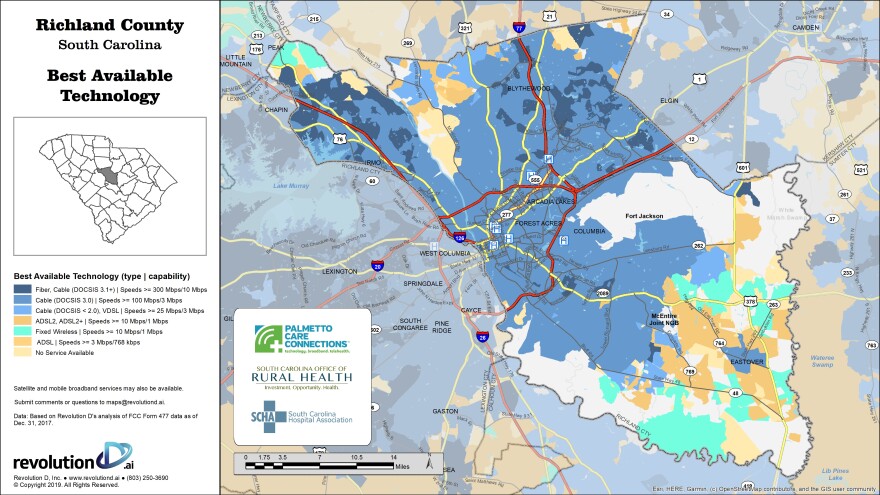

Pratt lives in Richland County, where according to a recent broadband mapping project, the majority of the area has access to high speed internet, offering data transfer rates greater or equal to 300 Mbps (megabits per second).

But for roughly 172,000 households (463,495 people) the mapping project indicates this technology is not available.

“It is a necessary piece of infrastructure that is critical if our state is going to grow and progress the way it should.”

Kathy Schwarting is CEO at Palmetto Care Connections (PPC), a nonprofit telehealth network in Bamberg County. The organization increases access to healthcare in rural areas of the state by infusing services via telehealth. But services are only effective if there is broadband to connect service providers with residents.

Schwarting said a lack of adequate broadband service could mean there is nothing, in an area, or there is only minimal internet service. To develop a full picture of what’s available in the state, in 2019, PPC partnered with the South Carolina Office of Rural Health (SCORH) and South Carolina Hospital Association (SCHA) to commission a comprehensive evaluation of residential broadband capabilities.

“Some of our communities with the highest levels of no access are Marlboro County, Chesterfield County, Beaufort and Oconee,” Schwarting said. Areas of need and the types and speed of internet in all 46 counties is available in two maps and viewable online.

Schwarting’s work focuses on broadband needs within the healthcare field, but she said the Coronavirus may be the thing to help “solidify” the need for broadband, which impacts many other fields of work.

“The lack of broadband access affects our state from an economic development standpoint, from an

It really stumps the rural communities because they can't do things as seamless as a lot of the urban areas

educational standpoint, our farming community, the healthcare community- it affects everybody.”

In Bamberg County, where PPC is located, Schwarting says students, teachers and parents are feeling the effects of inadequate broadband service.

Teachers “are making hard copies of homework assignments for the kids to do, and the parents are having to come pick those packets up. It really stumps the rural communities because they can’t do things as seamless as a lot of the urban areas,” she said.

To help close the digital divide between rural and urban students, the state’s Department of Education sends Wi-Fi-enabled school buses or mobile hotspots to various school districts across the state.

Why Rural Areas Lag In Broadband Access

Kathy Schwarting is CEO of Palmetto Care Connections. She oversees current programs and the strategic plan for PCC. In March, she talked with South Carolina Public Radio about why rural areas lag in broadband access and how stakeholders are getting creative and thinking “outside the box” to narrow digital divides in South Carolina and other states.

Despite current barriers, Schwarting said she is optimistic solving South Carolina’s broadband access problem can soon be a reality.

Thelisha Eaddy is a Reporter for South Carolina Public Radio. Follow Thelisha on Twitter @ThelishaEaddy.