They are not household names like the reporters who broke the Watergate story for the Washington Post, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

But five guys, former special agents who helped the FBI break the case, have quite a story to tell.

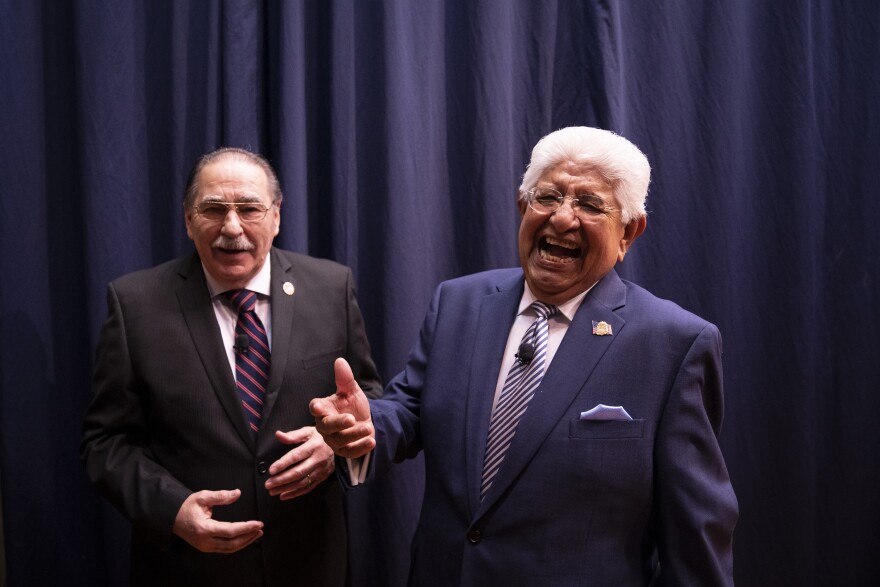

They shared it as they reunited for the first time in nearly 50 years at the 2020 Intelligence and Ethics Conference at the Citadel in Charleston in February.

"It was approximately 8 am Saturday, June 17th, 1972," recalled lead investigator Angelo Lano.

He was leaving for baseball practice with his sons when he got the call there had been a burglary at the Democratic National Committee Headquarters.

"You'll be home probably in about two hours," Lano remembered being told. The investigation spanned two years.

Lano says he met with the detectives who made the arrest and inspected what they seized from the burglars, including a fire alarm detection box with a dangling wire.

"One of the detectives thought it was a bomb," said Lano. "I told him no, there's a microphone at the end of the wire."

There was also a gym bag the men carried. Inside, Lano found cameras, dozens of rolls of film, and several telephone monitoring devices.

"I said, this isn't a routine burglary. These devices are used for intercepting communications."

Another former special agent, Paul Magallanes, tried to pry information from the burglars in Spanish. They were caught wearing business suits and rubber gloves. But the Cuban nationals refused to cooperate, despite being detained in what Magallanes describes as a daunting Washington, D.C. jail.

"I said, this isn't a routine burglary. These devices are used for intercepting communications."- lead FBI Watergate investigator Angelo Lano.

"Their demeanor was very flippant," Magallanes said. "They were all going to get off and they told me so."

The words of one of the burglars were particularly chilling.

"We're both working for the same man."

"What do you mean by that?" Magallanes pressed.

"Well, you know, we're working for the president."

Former FBI investigator John Mindermann was the weekend, off-duty case agent the day of the Watergate break-in. He says the crooks were caught, "as dirty as you get".

But how, with their radios and lookouts?

A former police officer himself, Mindermann explains it was a Friday night near Georgetown. He says cops were tied up with drinking and fighting at local night clubs.

Mindermann says a marked unit was initially dispatched, but the officers reported a "mechanical problem". It turns out, they ran out of gas. So, another group was called to respond; a sergeant and two officers working undercover nearby. One was dressed in women's clothing.

"They didn't make them out as cops," Mindermann said. "They didn't radio across the street to say the cops are here, dump everything and get out."

Mindermann credits metro police with securing the scene and preserving the evidence.

Then special agent Daniel Mahan interviewed many of the key government officials who later served time including: Charles Colson, special counsel to the president; G. Gordon Liddy, ex-White House staff; and John Dean, White House legal counsel.

But Mahan says from the beginning, there was something amiss. He and other agents had to follow new rules. For example, an attorney for the White House was required during all interviews.

The former FBI agents say that was simply unprecedented and flew in the face of their Quantico training. They were taught no attorneys were allowed unless the person had been convicted or wanted to confess.

"It didn't take an intellectual giant to figure out Dean was working for the White House," Mahan said. "He was present for the interviews."

Still, Magallanes was able to develop two key sources, Penny Gleason and Judy Hoback. Both worked for Nixon's Committee to Re-Elect the President. Both helped the FBI tie money from that committee to the Watergate burglary.

"She called me through my office and said listen, I didn't tell you anything because I was intimidated. I was scared," said Magallanes referring to his conversation with Gleason. "But I have lots to tell you."

Magallanes say Gleason agreed to talk, but under certain conditions and in the privacy of his car. It was summertime in the nation's capitol and as luck would have it, his car overheated.

"It's ridiculous," Magallanes said. "We can't go on like this. She has all this information and she's giving it to us."

So, Magallanes called his boss. The FBI rented a hotel room. There, he and another agent interviewed Gleason for six hours. He says she not only confirmed the money trail but told them files had been shredded

Their confidential interview, however, quickly turned up in the Washington Post. Magallanes was furious.

The newspaper had a source. It was later revealed that the FBI's second in command at the time, Mark Felt, was the secret informant. The paper's editors nicknamed him, "Deep Throat."

But Magallanes says those within the FBI called him something else.

"They called him the White Rat,"- former FBI special agent Paul Magallanes talking about the Washington Post source nicknamed "Deep Throat".

"They called him the white rat."

The former special agents have differing views on Felt. Magallanes, Lano and Mahan believe he was a traitor who just wanted be promoted but put their work and the lives of witnesses in jeopardy.

Mindermann and fellow investigator John Clynick suspect something else.

"He was seeing the FBI being prostituted by the White House," said Clynick.

"They were interfering or trying to interfere with our legitimate, worthwhile investigation. I'm sure that rubbed him the wrong way."

In all, 69 government officials were charged in connection to the Watergate scandal. 48 were found guilty.

President Nixon resigned August 9, 1974 saying he did not have the support of Congress he considered necessary and the nation would require.

"Public accountability changed completely after Watergate," said Clynick.

The timing of the reunion isn't lost on the group either. It follows the recent impeachment of President Donald Trump.

"Oh, I've had a lot of Deja vu," Mindermann said.

He helped secure the White House in the spring of 1973, collecting evidence under the orders of the attorney general. Mindermann says he did so despite what he calls the tirades of then president, Richard Nixon.

He recalls Nixon ranting on one ocassion, "This is terrible. These men are not criminal. You should not be here."

Mindermann also recounts a scene where he says the president grabbed one agent by the lapels, lifted him from the ground, and slammed him against a door.

"What do you do when you're being mugged by the president? Not much." -Former special FBI agent John Mindermann.

"What do you do when you're being mugged by the president," Mindermann said. "Not much."

Mindermann says the case if riddled with bizarre moments.

Yet, he and the others feel a sense of pride, a commitment, and a connection to something bigger themselves.

"You never think you'll be involved in anything approaching this level," Mindermann said.

The now silver haired, former FBI agents weren't seeking glory. They never imagined a place in history.

After the investigation, they quietly went their separate ways, disappearing into obscurity.

But looking back, they say they were just doing their jobs, and doing their best, to do what they believed was right.